Heather Barnett

Observation Station

This conversation with Heather Barnett took place in April 2022 while she was participating in the Machine Wilderness ARTIS residency programme in Amsterdam. Heather is an artist, researcher and educator. She works with biological organisms and imaging technologies, exploring how we observe, understand and relate to the world around us. Heather is interviewed by Maddie Rose Hills who is the curator and researcher of Mater.

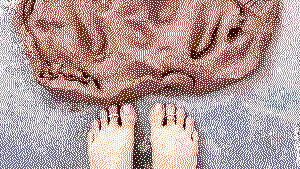

'Gorilla watching me, watching the ants’. Observing ant activity in the gorilla house, ARTIS, Amsterdam © Heather Barnett

Maddie Rose Hills: Heather, you work with natural phenomena and living systems, often in collaboration with scientists, artists, participants and organisms. Please can you tell me a bit about your relationship with these organisms and your approach to working with them?

Heather Barnett: I often work with organisms that many people know little about, the unsung heroes of the natural world. Conceptually I have a strong interest in ecology and biology and a motivation to live better with and on our planet. I think we’re the worst species in terms of how we look after our habitat, so I have huge respect for organisms which operate more reciprocally in their world. I also want to challenge human exceptionalism and expose other forms of intelligent life.

As an artist you're manipulating something to get it to perform for you: you're carving a piece of marble, you're marking a page with charcoal, or working with data to help communicate something. Whatever you work with it is important to understand your materials. Working with a living system even more so, it has its own agenda, layers of subjective requirements and environmental needs. It also raises ethical questions as to how I work with a living thing and the nature of that relationship.

'Ants washing antennae after feeding'

I'm not manipulating the organisms on a molecular scale in the way many bioartists do, working at a genetic level or using biotechnologies such as CRISPR. But I am often working outside of a natural habitat and taking things out of context. With the slime mould I create artificial environments for it to navigate and try to influence its growth patterns based on my knowledge of what it likes and dislikes. I'm not interested in controlling the outcome, but in creating the conditions that will lead to an emergent property, for something unforeseen to occur.

The Physarum Experiments, Study No: 019, The Maze (film still) © Heather Barnett

Resilient Topographies #1: the peninsula of Paljassaare (film still) © Heather Barnett (in collaboration with ecologic studio)

How do these organisms help question the ways intelligence is defined?

There is a huge amount of interesting work around biological computation and definitions of intelligence in machine learning - the learning, memory and perceiving that we are trying to replicate in artificial intelligence. How we define intelligence has been called into question in terms of how artificial intelligence can (or cannot) understand context, meaning and inference, rather than merely recognise pattern. The same questions are asked with the slime mould, which has demonstrated that it can learn from experience, it can hold that learning within its body even during a dormant state, it can pass that learning onto another slime mould that hasn’t been habituated in the same way, and scientists still do not really know what drives this behaviour. I love the fact that this little blob that most people ignore on the bottom of a log somewhere in a wood is spurring all this human curiosity and enquiry.

The Physarum Experiments, Study No: 026, Intraspecies Fusion (film still) © Heather Barnett

When I asked you to be involved in this project, you mentioned that you are hesitant to describe your practice as working with materials. How do you refer to these organisms?

I would never naturally choose to say I work with living materials, but I would say I work with living systems or organisms in different ways: as material, model and metaphor. With something living it is not a material that can be manipulated into shape, but an autonomous agent that presents particular behaviours and characteristics that can be worked with. So in a sense I am sculpting indirectly with inherent characteristics, through an understanding of its needs and preferences, and the placing of attractants or repellents in its environment. These systems are also conceptual models for looking at other kinds of networked systems or metaphorical models for exploring the mechanisms of collective coordination.

It’s interesting what you do with the knowledge gained from observing these organisms. Your workshops for example are about learning from organisms. Do you think it is possible for humans to ingrain those ways of behaving, because they throw up questions of collectivism and connectedness, but I don't know how capable we are of that.

The short answer is no. The longer answer is about why it's worth trying to do something that is an impossibility. I don't think we can easily let go of being human, but trying to let go of human-centric traits, such as our modes of communication, and engaging with other forms of perception can raise questions about what it is to be a human animal. The Being Slime Mould experiment was developed as a way to engage experientially with other ways of being and communicating. Initially created around nine years ago it has since evolved over time and become truer to how slime mould operates. People are given behavioural rules and tasked to become a human ‘supercell’ and navigate their terrain as a single collective body. We reduce vision because humans are very visual and slime mould is chemically sensing its environment. Humans use language to describe, define and name, so you cannot speak but must find other forms to communicate information. It's purposefully playful and it's utterly absurd. It's destined to fail.

It is a challenge to human ego. Can a bunch of humans communicate as effectively as a slime mould? Can a group of complex multicellular bodies with highly differentiated organs cooperate better than a single celled amoeba without any sensory organs or a brain? Well, no, they can't. We intellectualise things a lot, but I'm interested in thinking through doing. I see Being Slime Mould as a form of practical philosophy, a way of asking questions through operating in a different realm.

Heather observing ant activity in the gorilla house, ARTIS, Amsterdam © Theun Karelse

I came to your ant workshop for your current Machine Wilderness residency. The workshop was about observing ants. How they go off and look in all directions, it's almost like what the slime mould is doing.

A slime mould cell is essentially millions of nuclei sharing a cell membrane, all shuttling around in a dynamic network of veins and operating as one through chemical signalling. An ant is a complex organism with a brain, but the colony is many thousands of ants all operating together. Both are emergent systems, where complexity arises from multiple interactions between many individuals. From dynamic situations things emerge that are greater than the sum of their parts. Think about our cities, infrastructures, distribution, the complexity of the information on social media and how certain voices or signals are amplified, or the infiltration of fake news. All these systems are interlinked.

'Ant spotting’. Tuning into ant activity at ARTIS, Amsterdam © Heather Barnett

Life drawing workshop, tuning into the social behaviour of the ant colony, the gorilla house, ARTIS, Amsterdam © Theun Karelse

These natural systems are hugely resilient. If you knock out part of an ant colony, the ants will self-organise around the problem to repair it. Same with a termite mound, a bee hive or a slime mould cell. They're highly adaptive and responsive. Human infrastructures are not so flexible and they do not operate in dialogue with the environment – usually the exact opposite. There are serious lessons that society can learn from looking at emergent living systems.

Can you tell me more about your plans for the residency?

For Machine Wilderness (at ARTIS Amsterdam Royal Zoo), my aim was to focus on the animals that are not part of the collection. There is a tension in any zoo between providing a visitor experience, the spectacle of encounters with exotic creatures, balanced with the agenda for conservation, education and engagement. There's a lot of complexity around the display of animals and the efforts to provide them with adequate habitat and stimulation. The zoo is a machine for observation, set up to frame animal behaviour. People don't want to just look at the animal, they want the animal to look back, they want a connection.

The ants are everywhere and they're highly opportunistic. They will establish nesting sites in conducive environments, and depending on where they are at ARTIS, they're either ignored or seen as pests. I wanted to draw attention to these incidental creatures living in the zoo. I found some active colonies in the gorilla house, living in the plantation borders around the enclosure, which presented an interesting juxtaposition - two very different social creatures. People are also already slowed down in the mode of watching the gorillas, so are well placed to shift their attention further to a smaller scale. I've created some makeshift observation stations in the undergrowth, which provide a small stage for the ants to present themselves. The intention is to draw out the behaviour of the ants and draw in the curiosity of the visitors – an open invitation to observe and discuss what they see. The observation stations use devices to amplify the behaviour of the ants, such as magnifying lenses or an endoscopy camera which permits closer viewing. These imaging technologies act as an interface between two very different spatio-temporal worlds and they help mediate between two different species – human and ant. They enable us to observe behaviour we would otherwise not see. The experience of the zoo is a constructed mediation. The enclosures are designed to satisfy the needs of the organism, but they are also designed to satisfy the viewing needs of a curious public. It's about the act of looking, and through which frame, and what we expect in return. I’m trying to shift perspective.

I see myself as a storyteller in a way, a spokesperson for these incredible natural phenomena that we often don't take notice of. As humans, we see ourselves as separate from the land we rely on and superior to all other forms of life. It's all a complex ecosystem and we are but one part of it. We need to recognise that and respect the multifaceted interrelationships.

Scaling down observation to observe the patterns of behaviour in the undergrowth. ARTIS, Amsterdam © Heather Barnett

Heather Barnett is an artist, researcher and educator working with natural phenomena and living systems, often in collaboration with scientists, artists, participants and organisms. Using diverse media including printmaking, photography, animation, video, installation and participatory experimentation, and working with biological materials and imaging technologies, her work explores how we observe, understand and relate to the world around us. Recent work centres around nonhuman intelligence, collective behaviour and distributed knowledge systems, including The Realm immersive interactive experience; The Physarum Experiments, an ongoing ‘collaboration’ with an intelligent slime mould; Animal Collectives Leverhulme Artist in Residence with Swansea University; and a series of collective interdisciplinary biosocial experiments including Nodes and Networks and Crowd Control.

Machine Wilderness is an artistic field programme exploring new relationships between people, our technologies and the natural world. Machines have become an intrinsic part of our world (according to some a second nature). But their presence is highly disruptive to the worlds of other beings on land, in the seas and skies. How can technologies relate more symbiotically with other living beings?

In 2022, eight artists joined the Machine Wilderness residency programme exploring the rich and diverse worlds of animals, plants and microbes in ARTIS and MICROPIA. From March till June artists are each experimenting for a number of weeks in the park to get closer to the lives of other creatures and reveal hidden worlds. Visitors can see them at work during their research or learn more in artists' presentations. By exploring the relations between technology and other life forms we investigate how animals and plants share signals, how they learn, set boundaries, or organize their lives. Through experiments and prototypes we try to find ways to engage with their worlds more deeply. Can machines help us rejoin the great conversation with life?

Residents: Driessen & Verstappen, Heather Barnett, Thomas Thwaites, Ivan Henriques, Antti Tenetz, Spela Petric and Ian Ingram.

Machine Wilderness is based on long-term research by Theun Karelse at FoAM and developed into a programme in collaboration with Alice Smits of Zone2Source. This programme is centred on public events and fieldwork sessions where teams of people with diverse backgrounds and ways of knowing develop methodologies and prototypes of wilderness machines that try to engage with local environmental complexity.

Heather participated in Machine Wilderness 2-14 April There will be a Closing Event on June 24, 2022: Machine Wilderness art-science fair at the Groote Museum